Our research

BHF-funded research is helping to improve and save the lives of people living with heart and circulatory diseases.

BHF's Health Analytics Team has brought together data that looks into how deprivation impacts heart and circulatory diseases in England.

Where you live, how much money you have, and your gender, ethnicity and age shouldn't affect the care you receive. But too often they do.

Our study brought together data to look at the differences in prevention, treatment and outcomes by levels of deprivation in England.

All these things can lead to poorer health outcomes.

There are estimated to be 6.4 million people living with heart and circulatory diseases in England today.

Many millions more have risk factors for these conditions, such as high blood pressure, raised cholesterol, obesity, and type 2 diabetes.

We also know that heart and circulatory diseases are strongly associated with health inequalities. For the first time, data has been brought together to look at the differences in prevention, treatment and outcomes by levels of deprivation in England.

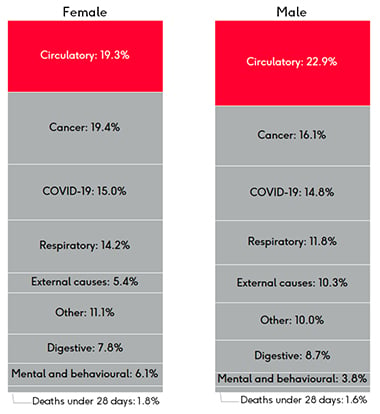

An estimated 6.4 million people are living with cardiovascular diseases in England today. Many millions more have risk factors for these conditions such as high blood pressure, raised cholesterol, obesity and type 2 diabetes. Although deaths from cardiovascular diseases have declined over the last few decades, these conditions still cause a quarter of all deaths in England and remain the leading cause of death globally.1

What’s more is that cardiovascular diseases are strongly associated with health inequalities, contributing to around one-fifth of the life expectancy gap between the most and least deprived quintiles in men and women (Figure 1).

There are differences between different popular groups in the prevalence, treatment and outcomes of cardiovascular diseases and their risk factors. This is because cardiovascular health is deeply connected to and affected by wider determinants of health. In other words, the disparities seen among people with cardiovascular diseases are driven by factors such as income, housing, education, the environment, and access to health and social care. People in more deprived areas develop multiple conditions 10-15 years earlier than in more affluent ones. They are also more likely to develop multiple conditions in the first place – 28% of people in the most deprived areas have four or more health conditions, compared to 16% in the most affluent.2

Figure 1. Percent contribution to life expectancy gap between the most deprived quintile and least deprived quintile of England, by condition, 2020-21.

Source: Office for Health Improvement and Disparities based on ONS death registration data (provisional for 2021) and 2020 mid year population estimates, and Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities Index of Multiple Deprivation, 2019, Breakdown of the life expectancy gap. Data may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Health inequalities are differences in health status, healthcare, and health-related risks between different population groups that are unfair and avoidable. They include:

The coronavirus pandemic has highlighted, and probably worsened, health inequalities across the country. This analysis examines the trends of inequalities in cardiovascular disease before the pandemic at multiple points on the patient pathway (Figure 2) focusing on prevention, detection & diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Due to disruption of services, care, and the suspension of some data collection during the early pandemic, we focused the analysis on data up to financial year 2019/20. This is the first holistic view of health inequalities across the CVD pathway, giving additional insight into not only where improvement is needed, but also indications of where there are data gaps and opportunities for further analysis.

Figure 2. The CVD pathway

2 The Richmond Group, Health Foundation (2019) The Multiple Conditions Guidebook

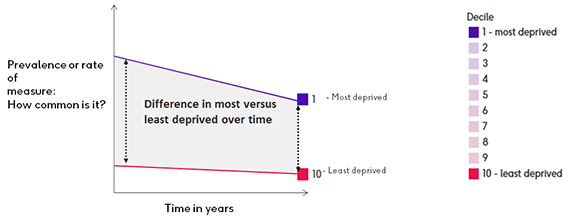

An indication of inequality by geography is the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD). It is the official measure of relative deprivation in England. We chose to use the IMD as it is a well-recognised, validated measure of deprivation that incorporates many of the wider determinants discussed above and is not limited to a simple ‘rich – poor’ income-based dimension. The IMD scores measure relative deprivation in a small area and it is important to note that the deprivation level does not apply to each individual living in an area.

The neighbourhood IMD scores are mapped to larger geographies, including upper tier local authorities (UTLA). This analysis uses deprivation deciles (scores from 1 to 10) based on the average IMD score for each UTLA (where 1 represents the most deprived areas and 10 represents the least deprived areas). Full methodology can be found in the appendix.

How to interpret the graphs

Prevention: modifiable risk factors for heart disease

Cardiovascular health is determined in part by a range of modifiable factors. In the UK, 80% of the cardiovascular disease burden can be attributed to modifiable risk factors, such as diet, smoking status and medically manageable risk factors like high blood pressure. These factors are often influenced by access to health and care services and the social, physical, and economic environments in which people live. This has an impact on our choices, behaviours, and exposure to risk.

An estimated 28% of adults in England are living with obesity and a further 36% have a body mass index (BMI) defined as overweight. Breaking this down into deprivation deciles, the most deprived decile has consistently had the highest proportion of adults classified as overweight or obese from 2015/16 to 2018/19. The overall trend of adults who are classified as overweight or obese is rising. But the gap between the most deprived and least deprived areas has remained the same, ranging from a 9% to 11% difference in prevalence over the time period (68% versus 58%, respectively, in 2018/19).

More than 1 in 5 adults are physically inactive in England. The prevalence of physical inactivity is again higher in the more deprived deciles. A similar gap of 8-10% occurred from 2015/16 to 2018/19, showing the more deprived deciles with a higher prevalence of inactivity (26% versus 17%, respectively, in 2018/19).

We know that smoking can lead to a heart attack or stroke. It is estimated that at least 12,000 deaths from cardiovascular diseases in England each year can be attributed to smoking. Like the prevalence of adults classified as overweight or obese and physically inactive, smoking prevalence in adults also varies by deprivation decile. While the trend of smoking has decreased from 2015-2019, the gap in prevalence from the most deprived to least deprived areas has remained largely the same, with some variation in deciles in between. In 2018, the prevalence of smoking was almost double in the most deprived population compared to the least deprived (18% versus 10%). The gap reduced slightly in 2019, however that was due to an increase in smoking prevalence in the least deprived area.

Detection and diagnosis

When it comes to other conditions (e.g. CVD or heart failure prevalence) the effect of deprivation is not clear, which may be due to the fact that since cardiovascular diseases tend to occur later in life, the age of a population might be outweighing the effect of deprivation levels.

In many cases the gap between the most and least deprived deciles is less than 1%, however these gaps can translate to tens of thousands of people. This is true for stroke/transient ischaemic attack, peripheral arterial disease, heart failure, and coronary heart disease (CHD).

The prevalence of diabetes has been rising since at least 2012, with a slight increase in the gap between the most and least deprived deciles. The 2nd most deprived area (decile 2) has the highest prevalence of diabetes.

The gap between the most and least deprived deciles has narrowed from 2015/16 to 2019/20 for hypertension to 0.13%. However, there was a larger gap, of 2%, between the least deprived decile (10) and 3rd least deprived decile. This shows that there is variation in prevalence across the country, but it is not clearly defined by deprivation.

In the case of both diabetes and hypertension, the most deprived areas have a higher prevalence compared to the least deprived. However, the relationship to deprivation overall isn’t as clear as it is for obesity, physical activity or smoking.

These risk factor data are from Quality Outcomes Framework (QOF), which is a voluntary annual reward and incentive programme for all GP practices in England to reward good practice. It is important to note that the data is not age-standardised and there is evidence of a wide variation among practices in the size of the gap between reported and estimated prevalence. For a number of conditions, deprived practices and areas are failing to identify all cases of disease within their practice populations.3 According to a King’s Fund report: “practices that performed better on QOF had more complete recording of disease prevalence after adjusting for other factors. This suggests that practices are not gaming by failing to register patients. A more likely explanation is that well-organised practices that are able to achieve better QOF scores may also be more systematic in their approach to case finding.”4

Treatment

Prescriptions

Overall, there are long term, sustained rises in prescribing of antihypertensive, heart failure drugs and lipid lowering drugs, reflecting the increasing burden of heart failure in the population and efforts to manage high rates of high-risk conditions. The decline in the use of diuretics, at least in the context of use in management of hypertension, could point to changes in the approach to management of hypertension, although growth in heart failure prevalence may be expected to counteract this decline in use of diuretics.

Slower growth in anti-anginals, beta-blockers and anticoagulants is perhaps surprising given the rapidly dropping prevalence of coronary heart disease across the UK but may be indicative of changes in management of the disease in primary care where the majority of prescriptions are issued. A significant fall in the prescribing of anti-platelet drugs is more consistent with falling coronary heart disease prevalence.

There are differences in prescription rates between decile of deprivation, but this varies based on the type of drug. Our analysis shows that the least deprived areas have the lowest prescription rates for many of the most prescribed CVD drugs (for a list of definitions see Appendix 2). Among the drugs where the least deprived areas have the lowest prescription rates were antiplatelets; beta-adrenoceptor blocking drugs; diuretics; hypertension and heart failure; lipid-regulating drugs; and nitrates, calcium-channel blockers, and other antianginal drugs. In each of these, the 2nd most deprived decile had the highest rate of prescriptions and there was consistently a gap between the most deprived and least deprived deciles.

The 10th (least deprived) decile has the highest rate for anti-arrhythmic drugs, which may be due to the higher prevalence of AF in these areas.

Hospital admissions

It is difficult to see clear inequality trends within cardiac hospital admissions data. We looked at elective admissions compared with emergency admissions by deprivation. In this context an ‘elective’ admission means an admission that is planned; generally speaking a patient will be admitted to hospital from a waiting list for a specific procedure following diagnostic tests and specialist consultation. An ‘emergency’ admission is an unplanned admission, where the patient has been admitted via A&E or referred urgently by their GP. A decision to admit a patient as an emergency is not always made for life-threatening reasons, but can be for urgent diagnostic procedures or observation.

In the graph below, you can see that the average CVD emergency admission rate is consistently higher for those in the most deprived areas when compared to the least deprived. The opposite is true for elective admissions, showing that the least deprived areas have higher rates than the most deprived areas, with a growing gap due to fewer admissions in the most deprived decile. However, the highest rates of elective admissions occur in the middle deciles (5, 6, and 7) and the lowest rates are in the 4th most deprived areas.

Inequalities across all admissions (not just cardiovascular) are more clear cut, showing that the most deprived areas have the highest emergency admissions rate and the least deprived areas have the lowest emergency admission rate.5

This apparent inequality in emergency admissions could be driven by a lack of access to primary care and there have been reports in the past of so-called ‘under doctoring’ in more deprived areas. Looking at the number of GPs per 100,000 population, there are significantly more GPs in the least deprived decile than all others. There does not appear to be, on the whole, a general relationship between relative deprivation and numbers of GPs. However, it should be noted that if GP capacity were related to need we would expect see a pattern of high number per 100,000 in the most deprived decile, and lower numbers in least deprived areas. This is not apparent here.

Number of GPs (headcount) per 100,000 people, by decile

Ischaemic heart disease, also called coronary heart disease, is when coronary arteries that supply the heart with oxygen-rich blood become narrowed by a build-up of fatty material. Coronary heart disease is the most common type of heart disease and if a blockage occurs it can cause a heart attack. It’s also the single biggest cause of premature death in England.

The gap in prevalence between the most and least deprived decile is less than 1%. However, the graphs below that show that the most deprived deciles have lower admissions rates from 2016-2019 for elective care when compared with the least deprived areas. The elective admissions rate for coronary heart disease is 17% higher in the least deprived areas compared to the most deprived. This suggests that people in the most deprived areas are not being referred as often for elective admissions.

Acute myocardial infarction, or heart attack, is a medical emergency when there is a sudden loss of blood flow to a part of the heart muscle. There are over 80,000 hospital admissions for heart attacks each year in England. The emergency admissions rate for heart attacks in 2019 were 30% higher in the 2nd most deprived decile and 16% higher in the most deprived decile compared to the least deprived decile.

There has been an effort in England to reduce emergency admissions. This has included primary care improvement policies, as 14% of emergency admissions in 2015/16 were for conditions that could be managed in primary care. However, the trend of increasing emergency admissions continues to grow. This makes it difficult for hospitals to reliably deliver elective care.6

A Nuffield Trust report reviewed initiatives that aimed to avoid hospital admissions. They found that the initiatives with the most positive outcomes are for condition-specific rehabilitation, such as pulmonary and cardiac rehabilitation.7 These improve quality of life and reduce hospital admissions.

Long-term management, support and outcomes

Cardiac rehabilitation

Cardiac rehabilitation is an evidence-based intervention, delivered by a multidisciplinary team, that is proven to be clinically and cost effective for improving physical and health-related quality of life outcomes after a cardiac event.8

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Clinical Guidance (CG172, CG94 and NG106) and leading British and European cardiovascular professional associations recommend that cardiac rehab should be offered to all eligible patients in a timely and appropriate manner, taking the form of group-, home- or web-based sessions and with a recommended minimum duration of eight weeks.

Cardiac rehab data comes from NACR, where a number of UTLAs had less than 30 patients total. These cannot be broken down by demographics in order to protect confidentiality and were therefore excluded from the analysis (Appendix 3).

On average, cardiac rehabilitation uptake hovers around 50%. The gap between the number of people who started cardiac rehab in the most versus least deprived areas has narrowed between 2015 and 2019 for White people, males, and females. In each of these, uptake within the least deprived decile has remained higher than in the most deprived area the majority of the time frame. The 4th most deprived decile consistently has the lowest percentage of people starting cardiac rehabilitation by ethnicity, sex, and marital status.

The percentage of people with a minority ethnic background in the most deprived areas who start cardiac rehab has fallen slightly over the last few years, resulting in an increased gap in uptake between the most and least deprived areas overall between 2015 and 2019. People in the most deprived decile who started rehab with a minority ethnic background had a lower uptake than White people in the same decile (43% versus 48%), whereas the difference by ethnicity in the least deprived decile was smaller (52% for people with a minority ethnic background versus 53% for White people).

Uptake is better overall for people who have a marital status of ‘partnered’ compared to those who are single. However, people in the most deprived areas have the same percentage of uptake (55%) whether they are single or partnered. In contrast, those in the least deprived areas have an 8% difference in uptake for those who are single (53%) versus partnered (61%). This could be due to people in more deprived areas lacking the flexibility to take time off work or childcare to prioritise their health, whether single or partnered. In the least deprived areas, people with partners may be more likely than their single counterparts to have the financial and social stability that allows them to attend cardiac rehabilitation programmes.

GP survey data

Patient activation measures describe the knowledge, skills and confidence a person has in managing their own health. It is widely acknowledged that those who have the confidence and skills to manager their own health are more likely to adopt healthy behaviour, to have better clinical outcomes and lower rates of hospitalisation, and to report higher levels of satisfaction with services.9

This extends to the management of long-term conditions where higher activation scores are positively correlated with adherence to treatment and condition monitoring, as well as obtaining regular care associated with the condition. The findings appear to be true for patients with a range of conditions and economic backgrounds, including disadvantaged and ethnically diverse groups and those who have less access to care.10

The GP Patient Survey is sent to over 2 million people across the UK and collects some basic patient activation data. It is carried out annually to capture the experience and demographics of patients at their GP practice. It helps monitor the quality of services over time.

Respondents are asked to report any long-term condition, and in the last three years around one-third of the respondents reported having CVD.

The survey captures patients’ confidence in managing their condition(s), with four options: very confident, fairly confident, not very confident, or not at all confident. Although this analysis includes people with any long-term condition, rather than CVD only, it is useful to examine this holistically since many people have multiple conditions and do not think of managing them in isolation. They are likely to consider having confidence in managing their conditions overall.

The survey data show a clear and consistent gap in confidence from 2018-2020, emphasising that those in the least deprived decile are most confident in managing their condition compared with those in the least deprived decile. In the least deprived areas, around 89% report feeling “very confident” or “fairly confident” managing their condition. In the most deprived areas, this drops to about 81%. A higher percentage of respondents (4%) in the most deprived decile report being “not at all confident” at managing their condition than those in the least deprived areas (2%).

Outcomes: mortality rates

Mortality rates from cardiovascular disease are clearly linked to deprivation deciles in the graphs below. The gap between the age-standardised death rates (ASDRs) for cardiovascular disease in all ages has increased slightly from 2013 to 2019 and is twice as high in under 75s for the most deprived versus least deprived areas.

ASDRs by sex

As mentioned previously, the slope index of inequality (SII) is another indication of inequality. Diverse populations, from very affluent to very deprived, tend to have wider health inequalities and, as a result, are more likely to have differences between the different population deciles. This would tend to be represented by a higher SII (with a lower ranking). More stable and uniform populations will tend to have a lower SII, reflecting smaller differences in population structure.11

It is known that women have a longer life expectancy than men. This gap persists within cardiovascular disease. Recent ASDRs (2017-19) for CVD in under 75s are higher for the most deprived areas when looking at SII and IMD indicators in both men and women. In the graphs you can see that the under 75s in UTLAs with higher SII rankings have higher ASDRs due to CVD. The same is true for the most deprived IMD deciles, marked in purple.

Middlesbrough had the highest SII for women, with a 10.0 year gap in life expectancy between the most and least deprived and a pre-mature CVD ASDR of 65.1 per 100,000. Windsor and Maidenhead had the lowest SII for women (less than 1 year difference in life expectancy between the most and least deprived) and a pre-mature CVD ASDR of 36.6 per 100,000.

While Middlesbrough had the second highest SII for men, the highest SII is in Stockton-on-Tees with a 12.6 year gap in life expectancy between the most and least deprived and a pre-mature CVD ASDR of 101.4 per 100,000. The lowest SII for men was in Shropshire with a 2.5 year gap between the most and least deprived and a pre-mature CVD ASDR of 82.9 per 100,000.

3, 4 King's Fund (2011) Impact of Quality and Outcomes Framework on health inequalities

5 Strategy Unit (2021) Socio-economic inequalities in access to planned hospital care: causes and consequences

6 Health Foundation (2018) Briefing: Emergency hospital admissions in England: which may be avoidable and how?

7 Imison C, Curry N, Holder H, Castle-Clark S, Nimmons D, Appleby J, Thorlby R and Lombardo S (2017) Shifting the balance of care: great expectations. Research Report. Nuffield Trust.

8 Anderson L, Oldridge N, Thompson D R, et al. (2016) Exercise based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis.

Rauch B, Davos C H, et al. (2016) The prognostic effect of cardiac rehabilitation in the era of acute revascularisation

9, 10 The King's Fund (2014) Supporting people to manage their health: An introduction to patient activation

11 NHS Hammersmith and Fulham, NHS Kensington and Chelsea, NHS Westminster Slope Index of inequality briefing

Health inequalities are complex, and the patient pathway for CVD patients is no exception. There are clear and consistent gaps across the pathway, particularly in the prevalence of modifiable risk factors, inconsistency in accessing elective hospital services, and poorer health outcomes in the most deprived areas.

The gaps are clearest in the prevention of modifiable risk factors early in the pathway. People in the most deprived areas have the highest prevalence of being classified as obese or overweight, physically inactive, and smoking.

When it comes to conditions, the prevalence and access to care is not consistently split by the most and least deprived. This could be due to many factors. As cardiovascular diseases tend to occur later in life, this could be due to the age of a population outweighing their deprivation levels. However, diabetes and hypertension both had higher prevalence rates in the most deprived areas compared to least deprived. Additionally, people in the most deprived areas have the least confidence in managing long-term conditions.

AF holds an inverse pattern throughout the pathway. People in the least deprived areas have the highest diagnosed prevalence of the disease, the highest elective and emergency hospital admissions rates, and a higher rate of prescriptions for drugs that treat AF compared to the most deprived areas.

In diseases with smaller differences in prevalence between the most and least deprived, like CHD, there were still differences in elective treatment, suggesting that planned care (arranged in advance, often following a GP referral) is skewed towards people living in the least deprived areas. People in the most deprived areas have lower hospital admissions rates for cardiovascular elective care and higher rates for emergency care. This likely leads to poorer health outcomes, clearly shown in the higher ASDRs in the most deprived areas in people under 75 years old and for all ages.

This elective versus emergency split in cardiovascular care is in line with the split for all hospital admissions, as shown in an analysis by The Strategy Unit. Their model suggests that increases in elective admissions leads to a reduction in emergency admissions, all other things being equal12. In addition to the moral justification for equal access to care, the model by The Strategy Unit suggests that some of the additional expenditure in planned care would be offset by reductions in the costs associated with emergency spells, as emergency spells are 25% more expensive than elective spells, on average.13

There are also clear inequalities in cardiac rehabilitation uptake between the most and least deprived. People in the most deprived areas often had a lower percentage of eligible people who started cardiac rehab compared to the least deprived. Within the least deprived decile, people with a minority ethnic background and females have lower uptake when compared to White people and males, respectively.

Focusing on prevention, education in managing long-term conditions (both in GP settings and cardiac rehab), and shifting hospital care from emergency to planned admissions in the most deprived areas could improve health outcomes in those populations.

12, 13 Strategy Unit (2021) Socio-economic inequalities in access to planned hospital care: causes and consequences

There are several limitations to this analysis. While we can gauge deprivation at the upper tier local authority level, this doesn't reveal the complex patterns of deprivation in smaller areas below this level. UTLAs (of which there are around 150) in many parts of England break down into smaller, lower-tier local authorities (meaning there are over 300 in total). There can be big disparities in wider determinants of health even within those much smaller local authorities. We used UTLA to maximise the amount of data that could be mapped across the patient pathway, but by examining inequalities in larger districts, it is likely that disparities within smaller geographies were hidden.

The SII and IMD were from 2015 and 2019, respectively. We used these most recent indicators of inequality across all trend analyses for consistency. However, areas of deprivation are likely to vary over time.

In most of this analysis there was not enough detail in the data to stratify by patient demographics, which we recognise as another limitation. In cardiac rehab data stratified by ethnicity, we were limited to grouping by White and people with a minority ethnic background due to small numbers. There were many cases where small numbers meant data had to be suppressed, which limited the analysis.

Similarly, the majority of the data used in this analysis did not have the detail for us to explore people with multiple conditions, which we know is an important contributing factor to people's overall health and is linked to deprivation14. Where we can, it is important to look at whole individuals across the patient pathway instead of parsing out individual patient characteristics.

More generally, we are limited to the data that is collected and so we reported primarily by geography, broken down by sex for ASDRs. The effects of deprivation may be compounded by other social factors. Intersectionality15 is a word used to describe how race, class, sex, and other individual characteristics overlap and combine with one another, which can affect outcomes. As highlighted by The Health Foundation and Marmot review 10 years on, we can see the effects of intersectionality within the socioeconomic inequalities in life expectancy16. While overall life expectancy has increased, socioeconomic inequalities in life expectancy have also increased for men and women over the last decade. Life expectancy has actually decreased for women in the most deprived decile between 2013-15 and 2016-18.

Data from the first wave of the pandemic showed that people in the most deprived areas were more likely to die from Covid-19 than those in the least deprived areas (133% more likely for women and 114% more likely for men)17, indicating that the pandemic has worsened inequalities. Throughout each wave of the pandemic, there were also clear ethnic disparities in deaths involving Covid-19, with many ethnic minority groups having worse outcomes compared to people with a White British background.18,19 When Omicron became the most common variant in early 2022, the pattern persisted with higher ASDRs involving Covid-19 for many ethnic minority groups compared with the White British group; ASDRs during this time period were highest for Bangladeshi and Pakistani groups.20

We know that multiple structural, contextual, and individual factors determine social disadvantage and that in turn this has an impact on health. Therefore, we need health services to collect and be transparent with demographic data in order to evaluate the effects of intersectionality. We also need more inclusive recruitment into research studies and clinical trials to create an evidence base representative of the general population, as outlined in the BHF's strategy for improving equality, diversity and inclusion.

14 The Health Foundation (2018) Understanding the health care needs of patients with multiple health conditions

15 An analytics framework coined by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw

16, 17 The Health Foundation (2020) Inequalities and deaths involved COVID-19: What the links between inequalities tell us

18 Equality Hub and Race Equality Unit (2021) Final report on progress to address Covid-19 health inequalities

19, 20 Office for National Statistics (2022) Dataset: Updating ethnic contrasts in deaths involving the coronavirus (COVID-19), England: 24 January 2020 to 16 February 2022

If we look at data across the cardiovascular disease pathway without analysing by deprivation and other individual factors, we risk overlooking important differences in cardiovascular disease and care. This analysis shows that the extent of health inequalities by level of deprivation varies throughout the cardiovascular pathway. Therefore, one overarching solution to reduce the gaps in health between the most and least deprived populations would not be effective. Instead, we need to determine the best approaches to reducing inequalities for each part of the cardiovascular disease pathway as well as the ripple effect those changes could have on the rest of the pathway.

It is key to consider the multi-faceted nature of health inequalities, which varies not just by level of deprivation but also by individual and population characteristics such as age, ethnicity, gender and how intersectionality can compound disadvantage and impact negatively on health. Individuals and specific populations should be at the centre of our health services.

Due to the inherent limitations of data, it is important to look beyond the datasets and connect health services with trusted local figures who can engage with people in specific minority communities, rather than relying on a one-size-fits-all solution across all areas with poor health outcomes. People in more deprived areas must be given information and tools to manage their cardiac conditions and risk factors that suit their specific needs, which may differ from the needs of those in less deprived areas. It is important to ensure that the most deprived populations have equitable access to surgeries, screenings, and emerging technologies in order to receive the same care as those in the least deprived populations.

We need to see:

BHF-funded research is helping to improve and save the lives of people living with heart and circulatory diseases.

Our statistics will help you to explore heart and circulatory data, including death rates, disease prevalence, treatment and costs.

We're striving to make things better - for our people, supporters, volunteers, researchers, and everyone affected by heart and circulatory diseases.