How autoimmune disease affects the heart

Learn how inflammation links conditions like lupus and rheumatoid arthritis to heart attacks and strokes, and what steps can be taken to reduce the risk.

When Barbara Colclough (pictured above with her husband Craig) had a heart attack at the age of 51, it was the last thing she expected.

“I woke up in the middle of the night feeling really unwell,” Barbara recounts. “I rushed to the toilet and threw up, and then a bit later the pain hit. It was like nothing I’d ever felt before. I called NHS 111 and I told them: ‘I feel like I’ve got an alien inside me!’ They called an ambulance for me straight away.”

Barbara had a stent fitted and spent a week in hospital. She had to be readmitted for a further week because she developed septicaemia (blood poisoning), and she still suffers from chest pain (angina), which restricts what she can do.

It was only much later that she discovered that lupus, a condition she had lived with for more than 20 years, meant that she was at an increased risk of heart disease.

Lupus increases heart disease risk

Lupus is an autoimmune disease – a term that covers a wide range of conditions in which the body's immune system mistakenly attacks its own healthy tissues causing inflammation and damage.

Lupus and several other conditions (see below) are ‘systemic autoimmune rheumatic conditions’ - ‘rheumatic’ means they affect the body’s connective tissues such as cartilage, bone, blood and fatty tissue. They also commonly cause inflammation throughout the body by affecting the immune system.

- lupus

- rheumatoid arthritis

- spondyloarthritis

- vasculitis

- Sjögren's syndrome.

But what is not widely known is that they are linked to a higher risk of heart and circulatory disease, including heart attack, stroke, heart failure and irregular heart rhythms (arrythmias).

Other autoimmune conditions, such as gout, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease (including Crohn's disease and colitis) also carry a higher risk.

Doctors do not fully understand how autoimmune conditions increase the risk of heart and circulatory diseases.

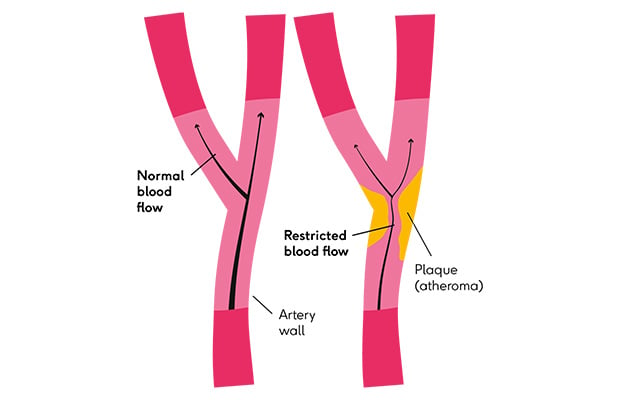

But it’s a combination of how they directly affect the heart and how chronic inflammation affects the blood and damages the lining of your blood vessels – this leads to fatty material building up and plaques (atherosclerosis) forming, which are responsible for heart attacks and strokes.

Dr Daniel Bromage, Clinical Senior Lecturer at King’s College London and Honorary Consultant Cardiologist at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, says: “Autoimmune conditions are known to be a risk factor for atherosclerosis, heart attacks and heart failure. I regularly see people with autoimmune conditions who end up in my cardiology clinic.

“I also have an inflammatory heart disease clinic, where we see lots of people with lupus and myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle) and related conditions. It is an issue that affects lots of people.”

Possible link to high cholesterol

Research suggests that autoimmune diseases might also lead to raised blood levels of bad cholesterol, and particularly to oxidised LDL (low-density lipoprotein) cholesterol, which is a harmful type of cholesterol that seems to contribute to the formation of fatty plaques in the arteries.

Some medicines used to treat autoimmune conditions have also been shown to raise cholesterol levels.

Because the exact reasons why these conditions can lead to heart disease are not fully understood, doctors are still trying to work out how to stop people like Barbara from developing a heart condition.

Dr Bromage says: “Quite a bit is known about the links between autoimmune conditions and cardiovascular diseases. But the mechanisms are still a bit elusive.”

The British Heart Foundation (BHF) is funding Dr Bromage and his team to do research to try to find out more about these underlying mechanisms.

Barbara lives with lupus and heart failure

This lack of understanding meant when Barbara was diagnosed with lupus, she did not know it would also increase her risk of developing a heart or circulatory disease.

For many years, she thought of lupus as a condition that only affected her skin and joints.

Barbara was diagnosed with lupus by chance. “I went to the doctor for something else and she noticed the butterfly-shaped rash on my face. She sent me to a dermatologist, and I was diagnosed with lupus. I’d never even heard of it.

“I was always tired, properly fatigued, and my joints ached, but I’d thought that was because I was always busy.

Barbara with her grandson, Jimmy, and her mother, Elsie. Photography by Daniel Dockeray.

“Since then, I’ve taken tablets for it which help to keep it under control, although I can’t do certain things, like sit in the sun. And the top of my mouth and my nails go black (a side effect of the lupus medication).”

Barbara is now living with heart failure following her heart attack.

This, coupled with her lupus, brings daily challenges. “The biggest thing is fatigue – which is different from being tired,” she explains.

“It’s hard to know if it’s the lupus or the heart failure. I have to pace myself. Some days are good, some days I can’t do anything.

“I used to be an autism support worker, but I had to stop work. In some ways, it’s been fortunate because I can spend more time with my grandkids, which I couldn’t do if I was still working. Although I can’t see them for too long, because they’re so full of energy and I get too exhausted.”

Simple activities like stairs and hills are difficult, and Barbara uses a walking stick due to low blood pressure, a side effect of her medication.

“The worst thing is when you feel like you want to do things, but you can’t,” she says. “The trouble is that the illness isn't visible and when you're holding on to a wall, not being able to breathe and feeling really sore, then people don't understand.”

I didn’t know lupus could affect my heart.

Barbara says even after her heart attack she got very little information about the wider impact of lupus on her body.

“There was never any information given about how it affected your organs, or your heart. I had to look for information myself.

“I’ve seen lots of doctors after my heart attack, and only 1 of them said ‘I see you’ve got lupus – did you know it can affect your heart?’ And I didn’t. I’d love to see more information out there because I don’t think people understand lupus.”

Dr Bromage agrees: “Our experience has been that people don’t know that they’re at increased risk of cardiovascular disease, and that has really big implications in terms of being able to prevent it.”

Understanding that having an autoimmune condition could put them at risk of heart attacks and strokes would mean that people with autoimmune diseases like Barbara have a chance to do something about it.

This might be making sure they go for an NHS Health Check, or having a conversation with their GP about whether they could benefit from taking statins that lower cholesterol.

Statins and a healthier lifestyle can reduce risk

Research shows that statins can reduce death rates among people with lupus and high cholesterol.

There’s also some evidence that statins could have a further positive impact by reducing the inflammation that comes with autoimmune conditions.

Lifestyle changes, such as switching to a Mediterranean-style diet or being more active, can also help to reduce your risk of heart disease.

It’s particularly important to give up smoking, since it’s known to make many autoimmune conditions worse, as well as increasing the risk of a heart attack or stroke.

But there’s also a need for more research to better understand exactly why autoimmune conditions lead to heart and circulatory problems, and why some people with these conditions suffer from heart problems while others do not.

Barbara with her granddaughter Susie.

Research into genetic alterations

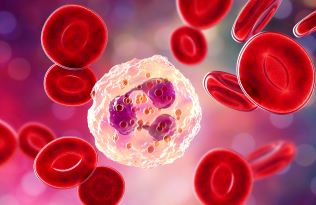

The BHF-funded research being carried out by Dr Bromage and colleagues is looking at one piece of the puzzle – a condition called CHIP (clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential) that’s found more often in people with autoimmune conditions.

It is caused by genetic mutations or 'mistakes' in stem cells in the bone marrow, which divide and create new blood cells throughout your life.

In people with CHIP, this affects the immune system cells, causing more inflammation, which can damage blood vessels and lead to the build-up of fatty material (plaques) that cause heart attacks and strokes.

According to research in the Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology in 2021, people with CHIP are twice as likely to develop a heart and circulatory disease as people without it – even when other risk factors are accounted for. CHIP is also more common as we get older, and in people who smoke or are living with obesity.

To understand the relationship between autoimmune conditions, CHIP and heart disease, Dr Bromage’s team is using cutting-edge techniques to study blood samples from people with rheumatoid arthritis.

People with CHIP are twice as likely to develop a heart and circulatory disease.

“We’re using advanced technologies to look at individual blood cells and measure CHIP. We’ll also look for the early signs of atherosclerosis (build-up of fatty material in the arteries), and see if we can see a relationship between that and having CHIP.

“We think there's a kind of vicious cycle where CHIP appears to predispose to atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular diseases, but these diseases and risk factors also increase the level of mutated cells.”

If the role of CHIP is better understood, then it could be used in future as a way of better understanding people’s individual heart disease risk, especially for those who also have autoimmune conditions

“We could potentially incorporate CHIP into existing heart disease risk scores, like QRISK, to identify those at highest risk and ensure they receive appropriate preventative treatments, such as statins, more proactively,” says Dr Bromage.

Anti-inflammatory drugs and new therapies

Another exciting area of research is using treatments that have been developed for other conditions.

One example is the anti-inflammatory drug colchicine used for gout, which Dr Bromage says has shown some promise in reducing issues like heart attack and stroke events in people with CHIP.

“This raises the possibility of using this treatment for heart protection, perhaps targeted at people who we know have CHIP.”

Looking further ahead, Dr Bromage sees the potential for new, targeted treatments aimed at reducing CHIP or counteracting its harmful effects.

“Understanding the specific gene mutations and how they contribute to inflammation and heart disease could pave the way for developing therapies that directly target CHIP itself.”

Despite the challenges of living with both lupus and heart failure, Barbara remains positive. She tries to stay as active as she can and enjoys taking her dog Casper for a walk by the sea near her home in Cumbria.

Barbara with her husband, Craig, and her dog, Casper.

“You’ve just got to take each day as it comes and keep smiling,” she advises. “Listen to your body and learn to say no. Having good family and friends who understand is so important. Life’s too short, you’ve got to enjoy it.

“If I can help other people by telling my story, then that’s something, isn’t it?” she says with a smile.

“More understanding and more information – that’s what’s needed.”

BHF is funding 3 studies into autoimmune conditions

1. CHIP, rheumatic autoimmune diseases and heart disease

Dr Bromage and his colleagues are in the first year of their 3-year project to better understand the role that CHIP plays in linking rheumatic autoimmune diseases, like rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, to heart and circulatory disease.

They are recruiting patients at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and will look at samples from 84 men and women, from a range of different ethnic backgrounds.

2. Lupus and fatty molecules in the blood

Professor Anna Nicolaou and her team at the University of Manchester have previously shown that people with lupus have higher levels of specific fatty molecules in their blood, and that these molecules can affect how our blood vessels constrict and relax.

They are currently in the final stages of a project looking at exactly how the fat molecules affect blood vessel health, as well as studying women with lupus to see what’s happening in the arteries and the fatty tissue surrounding blood vessels. This could lead to new treatments in future.

3. Autoimmune disease and dilated cardiomyopathy

At Queen Mary University of London, Professor Federica Marelli-Berg is working to understand how autoimmune disease can lead to dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) in some people.

DCM is a condition where the heart becomes enlarged and floppy, meaning it cannot pump blood very well.

They are looking at specific immune cells, which seem to attack the heart, to see if they can be used to diagnose and predict the progression of DCM. They are also looking at potential new treatments that could stop these cells from getting to the heart.

What to read next...

More useful information

Psoriatic arthritis and my heart

Blocked arteries: what are the signs and symptoms?