Inflammation: what is it, and how does it affect the heart?

Inflammation is part of the body’s healing response, but it can also cause serious disease. Dr Phoebe Kitscha explains what inflammation is and the latest research on it.

What's on this page:

What is inflammation?

- What is inflammation, and can it be dangerous?

- What is acute inflammation vs chronic inflammation?

- Can inflammation lead to a heart attack or stroke?

The latest research on inflammation

- Inflammation and heart disease

- Arthritis and heart disease

- Which people with arthritis are at risk of heart attacks?

- How does lupus affect blood vessels?

- Covid-19, inflammation and the heart

Want to get fit and healthy?

Sign up to our fortnightly Heart Matters newsletter to receive healthy recipes, new activity ideas, and expert tips for managing your health. Joining is free and takes two minutes.

I’d like to sign upWhat is inflammation?

What is inflammation, and can it be dangerous?

Inflammation is a part of the body’s healing process - it is a vital part of how the immune system works to protect and repair your body, helping to fight off infection and heal injury.

But there is also a darker side to inflammation – despite its useful effects, inflammation can also lead to diseases, or increase complications from them, including heart and circulatory diseases.

What is acute inflammation vs chronic inflammation?

Inflammation can be acute (short-term) or chronic (long-lasting). Acute inflammation is the body’s initial response when you have an injury or illness – think of the redness and swelling you see when you get a cut or splinter. The redness you might see around an injury is caused by increased blood flow.

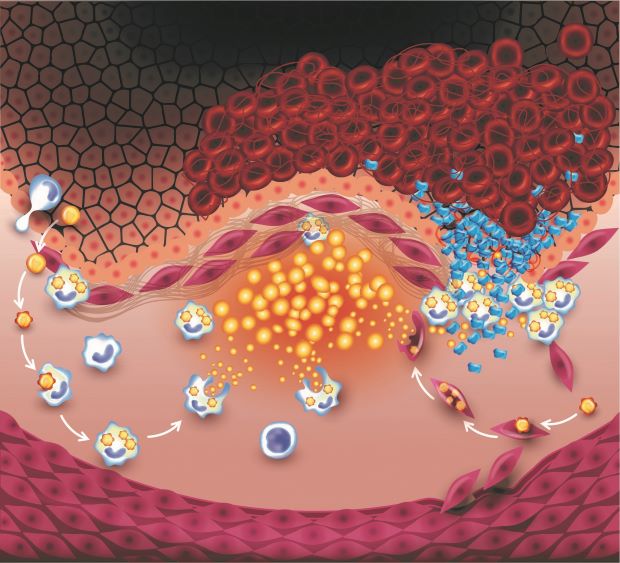

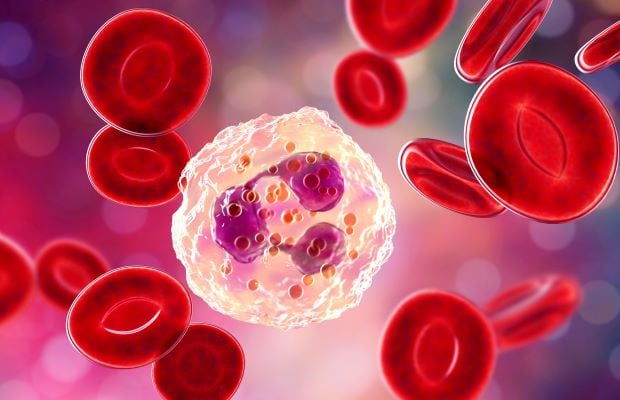

Our immune system responds to damage, or to harmful microbes, by releasing molecules which help to widen blood vessels and bring other immune cells to the threat. When this happens, the blood vessels also become “leaky” so that the immune cells can get to where they are needed – this “leaking” is what causes swelling, as fluid escapes from your blood and into your tissues. Some of these inflammatory signals can also act as pain signals. For example, the molecule bradykinin is released by activated immune cells in response to damage and helps to open up blood vessels – but it can also cause pain by interacting with nerve cells.

Normally, the acute phase of inflammation lasts only a few days, as different immune cells work to tackle the damage or infection and kickstart repair processes. But inflammation can also become chronic – where prolonged activation of these normally protective processes starts to damage the body.

Can inflammation lead to a heart attack or stroke?

Chronic inflammation is a culprit in many heart and circulatory conditions, including atherosclerosis, which can lead to heart attacks and strokes.

Atherosclerosis is where fatty plaques develop in the walls of our arteries. If the cells which line our arteries become damaged (for example, by smoking or high blood pressure), the resulting inflammation can allow fat molecules and immune cells to start building up in the artery wall.

To make matters worse, over time the immune response to this build-up contributes to the artery becoming hardened and narrowed, so less blood can get through. When this happens in the arteries which supply the heart, this can cause angina (chest pain).

Inflammation in the plaque itself can also make it more likely to burst, blocking the flow of blood and leading to a heart attack or, if it happens in the arteries supplying the brain, a stroke.

Immune cells (large blue cells shown above) cross from the blood stream into the artery wall, and take up fat molecules (yellow above). Smooth muscle cells in the artery wall (the purple cells above) can also take up the fat molecules. This cycle of inflammation can lead to the plaque rupturing, and the formation of a clot (red cells shown top right) which blocks blood flow.

The latest research on inflammation

Inflammation and heart disease

BHF-funded research is helping us to identify potential ways to tackle inflammation and the way it can contribute to heart and circulatory diseases. BHF Professor Ziad Mallat’s research is focussed on better understanding the inflammatory response in atherosclerosis and finding ways to target it. Previously, his team found that immune cells called Tregs (short for regulatory T cells), which help to dampen down inflammation, can limit atherosclerosis in mice. They are continuing to investigate how different types of immune cells are involved in blood vessel inflammation and the development of atherosclerosis.

A team of researchers led by Professor Mallat has been shortlisted for the BHF’s Big Beat Challenge, with a proposal to use cutting-edge technologies to build the first 3D “map” of atherosclerosis in humans, aiming to gain fundamental new knowledge about its links with the inflammatory and immune responses. It’s hoped that this could reveal new targets for treatments or even a vaccine to help tackle atherosclerosis – ultimately, helping to prevent heart attacks and strokes. The Big Beat Challenge is our largest ever research award – up to £30m – and the winner will be announced in early 2022.

Arthritis and heart disease

Chronic inflammation can also be caused by autoimmune diseases, where the immune system mistakenly attacks the body. People with these conditions often have increased levels of signalling molecules released by immune cells, called cytokines, in their body. For example, a cytokine called interleukin-6 (IL-6) plays a vital role in the initial inflammatory response to an infection, but is also found at increased levels in the blood and joints of people with rheumatoid arthritis.

Previous research led by BHF Professor John Danesh has also shown that having high levels of IL-6 in the blood over time is linked to a higher risk of developing coronary heart disease.

Which people with arthritis are at risk of heart attacks?

It’s thought that differences in cytokine levels contribute to why people with chronic inflammatory joint diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, are at a higher risk of coronary heart disease. But the usual ways of estimating a person’s risk of heart and circulatory disease, based on factors such as cholesterol levels, blood pressure or having other conditions like diabetes, don’t seem to be as good a way of predicting whether people with rheumatoid arthritis will develop coronary heart disease.

With BHF funding, Dr John Bowes and his team at the University of Manchester are aiming to use the genetic information of thousands of people to develop a screening tool to more accurately predict this risk. They will also look for genetic factors that link heart disease with arthritis and look at potential reasons why these two diseases often occur together. For example, whether genetic differences linked to the gene for the IL-6 receptor (which IL-6 interacts with to have its effects) could play a role. Their results could pave the way to preventing premature deaths of people with rheumatoid arthritis, by improving our understanding of the genetic links with heart disease, and helping to improve how doctors identify those most at risk.

How does lupus affect blood vessels?

Lupus, also called systemic lupus erythematosus, or SLE, is another autoimmune disease. It involves chronic inflammation throughout the body, causing symptoms like joint pain, skin rashes and tiredness, and mainly affects younger women. It is also linked to an increased risk of conditions, such as high blood pressure, kidney disease and vascular dementia, possibly because it can cause inflammation of the blood vessels (vasculitis).

Professor Anna Nicolaou and her team at the University of Manchester have already shown that people with lupus have higher amounts of fatty molecules in their blood, which are linked to the inflammatory response. These can also affect how the cells lining our blood vessels work – for example, how they relax and contract to regulate blood flow, and whether they release substances to help limit inflammation and clotting. Now, with BHF funding, the researchers are examining how these differences are linked to blood vessel health in 40 women with lupus, comparing them to 40 women without lupus. They will also carry out lab experiments to examine in detail how these fat molecules affect blood vessel function. They hope that their results will improve understanding of exactly what’s causing blood vessel damage, and could lead to the development of much-needed treatments.

Covid-19, inflammation, and the heart

Having Covid-19 can affect the heart and blood vessels. For example, in a small number of severe cases, it can cause inflammation of the heart muscle (myocarditis) or inflammation of the heart lining (pericarditis). This is likely to be connected to the body’s immune response to the virus.

- Find out more information about coronavirus and how it can affect the heart

Remember the cytokine called IL-6 – the signalling molecule that is important in the initial inflammatory response to an infection, but is also linked to the development of rheumatoid arthritis? In people with Covid-19, having high levels of IL-6 in the blood is associated with an increased risk of severe complications such as clotting in the lungs. The arthritis drug tocilizumab (which works by blocking the effects of IL-6) is now being used to help improve survival in people with severe Covid-19.

BHF-funded researcher Dr Sanjay Sinha and his team at the University of Cambridge are using stem cell ‘heart-in-a-dish’ technology – originally created to explore potential treatments for heart failure – to help understand how Covid-19 impacts the heart. Using blood samples from people with Covid-19, they are looking at how cytokines produced as part of the immune response to the virus affect lab-grown heart muscle. This research could lead to vital new knowledge about how Covid-19 can impact the heart, and how this heart-in-a-dish technique could be used to help test potential drugs to prevent these effects.

What to read next...

Anti-inflammatory diet: what you need to know

More useful information

10 signs you might have heart disease

How autoimmune disease affects your heart

Can't get through to your GP?