In terms of what the British Heart Foundation funds, the clue is in the name, but there’s more to us than just the heart. Heart and circulatory diseases cover a range of conditions that are often connected to other ailments. This means our research delves into all sorts of diseases. Here are a few new projects we’re excited to watch unfold.

1. How does lupus alter blood vessel health?

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), often called lupus, is an autoimmune disease (where the immune system attacks the body). Did you know people with lupus are at increased risk of heart and circulatory diseases, like high blood pressure, kidney disease and vascular dementia?

Research suggests that these diseases develop differently in people with lupus, compared to those without lupus. Professor Nicolaou and her team have already shown that people with lupus have higher amounts of certain types of fat molecules in their blood. Now, they plan to study blood and tissue samples donated by 40 people with the disease and 40 people without the disease to understand how these differences may be linked to blood vessel health.

Their discoveries could help determine how fat molecules may damage blood vessels in this group of people, and ultimately could lead to the development of much-needed treatments.

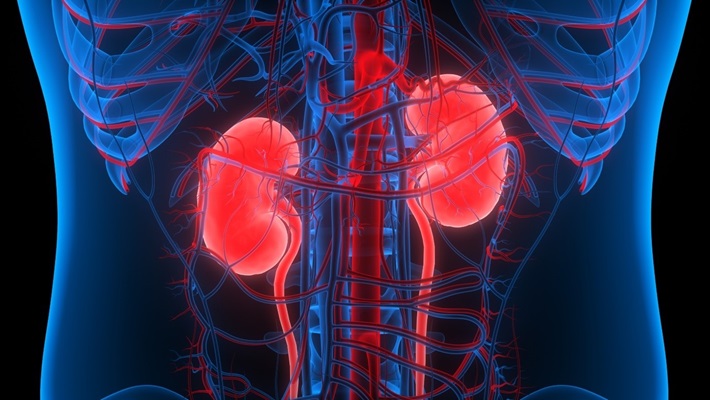

2. How the kidneys and brain talk to each other

There is an urgent need for new treatments for people who have high blood pressure, as some don’t respond to current drugs. Blood pressure is partly controlled by ‘conversations’ between the kidneys and the brain. The brain receives information from the kidneys and then tells the kidneys how much water to retain in the blood. When water is kept in the blood, pressure is raised, and when it is removed, pressure is lowered.

In people with high blood pressure, the brain sometimes gives kidneys the wrong instruction: to keep water in the blood, rather than remove it, which can increase blood pressure even higher.

Treatments have been developed that disconnect this faulty communication, but they work by destroying nerves in the kidney and have had mixed results. Dr Susan Pyner and her team aim to find out which kidney nerves are most important for sending signals to the brain about blood pressure, so they can be targeted alone.

They plan to track which nerves are involved by using a ‘tracer’ that can be seen with a microscope. The results could lead to more effective treatments for people with high blood pressure.

3. The link between diabetes and valve disease

People with aortic stenosis, when the aortic valve stiffens, often also have type 2 diabetes. Having diabetes can affect how well people recover from having their aortic valve replaced, but it’s not known why. The heart can burn fat or sugars for energy. Usually it burns fat, but in people with aortic stenosis, the heart switches to sugar. In people with type 2 diabetes, the heart prefers to burn fat for energy. But it is not yet clear what happens to the heart’s energy source in people who have both conditions.

Dr Eylem Levelt and her team have been awarded funding to follow 160 people (half with type 2 diabetes and half without) who are scheduled to undergo aortic valve replacement. One of their aims is to find out whether aortic stenosis and diabetes work together to create a harmful fat and sugar environment in the body. If so, this could be what is leading to the damaged heart muscle that prevents healthy recovery after aortic valve replacement surgery.

Some newer treatments for aortic stenosis work by shifting the heart’s energy use towards burning fat rather than sugar. This study will provide important evidence about whether these treatments would be safe in people with aortic stenosis and diabetes, due to potential differences in heart metabolism.

4. Can an iron test improve surgical outcomes?

Up to 50% of people who have heart surgery may have iron deficiency, often leading to blood transfusions, longer stays in intensive care and poorer recovery. Dr Pierpaolo Pellicori and team will investigate whether people should be routinely tested and treated for iron deficiency before heart surgery and what test would be most effective.

500 people who have planned heart surgery will have a number of blood tests carried out to assess whether they have iron deficiency. They will then be followed up for 30 days to see whether they needed a transfusion and how long they were in intensive care and other clinical factors. This will confirm how common iron deficiency is in this group.

The results will be compared with that of bone marrow biopsies taken during heart surgery, which is currently the gold standard test for iron deficiency. This will show whether the less invasive blood tests are as effective as the bone marrow sampling method. The team will also test whether giving iron treatment before surgery can help to improve these measures – a vital first step before a larger trial to conclusively test whether iron treatment could help improve outcomes from heart surgery.

Covid-19 has put us under serious financial strain. But finding answers for people with heart and circulatory disease remains our number one priority, which is why we’re working hard to continue funding the best research with the money we have.

Help us reach our goal of beating heartbreak forever.

Donate