Can vagus nerve stimulation make it easier to exercise?

We investigate recent reports that suggest a new study has found stimulating the vagus nerve can increase your VO2 max and improve your ability to exercise.

Want to enjoy the benefits of staying active but find exercising difficult? An electric shock to the ear could help, according to recent headlines.

In July, UK news outlets reported that a study had found that stimulating a large nerve called the vagus nerve can help people exercise more intensely.

This could potentially help people with conditions that make it harder to exercise, such as heart failure or chest pain (angina), continue to stay active and look after their heart.

In the study, healthy people were asked to wear a device on both ears for 30 minutes a day for a week that sent a small electrical current to increase the activity of the vagus nerve.

The researchers reported that this increased the amount of oxygen their body used during exercise and helped them work harder while exercising.

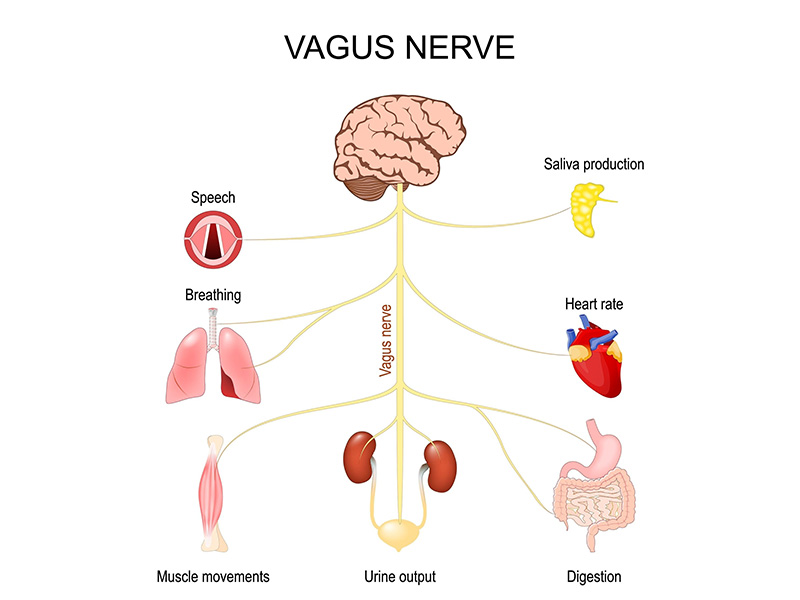

What is the vagus nerve?

The vagus nerve carries signals from your brain to lots of different parts of your body. This controls important functions like your heart rate, breathing and digestion.

It plays an important role in your parasympathetic nervous system, which helps you relax and slows down your heart rate when you’re resting. And it may also help to regulate inflammation, which is your body’s response to illness or injury.

Some research suggests that increasing the activity of the vagus nerve by stimulating it with a mild electrical current may help to treat epilepsy, depression, migraines and headaches. But it’s thought that vagus nerve stimulation may come with other benefits too.

So, when a new study funded by British Heart Foundation (BHF) and published in the European Heart Journal suggested that stimulating the vagus nerve could help people do more exercise, there was a lot of media interest.

Can vagus nerve stimulation increase VO2 max?

Researchers from the UK looked at how vagus nerve stimulation affected 28 healthy people’s VO2 max – the maximum amount of oxygen the body can use during the maximum intensity of an exercise.

A higher VO2 max means your body is using oxygen more efficiently and is a sign of a higher level of physical fitness.

They found that after wearing the vagus nerve stimulation device for half an hour every day for a week, the participants’ VO2 max was 3.8 per cent higher on average during peak exercise than it was before they used the device.

Their maximum heart rate and breathing rate also increased by 4 heart beats and 4 breaths a minute during exercise – showing they were working harder.

And when they switched to wearing a dummy device with no electrical current for the same amount of time and at the same intensity, there was no change to their VO2 max, heart rate and breathing rate.

The researchers concluded that the participants were able to do more intense exercise after wearing the real vagus nerve stimulation device than they were after wearing the dummy device – likely due to their increased VO2 max, heart rate and breathing rate.

Does vagus nerve stimulation reduce inflammation?

The researchers also took blood samples from 5 people in the study to see how vagus nerve stimulation affected markers of inflammation in their blood.

Inflammation is part of your body’s healing response, but too much inflammation over a long time has been linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

The study found that these people had less signs of inflammation in their blood after using the device than they did before, which suggests that increasing the activity of the vagus nerve could also reduce inflammation.

What do the researchers say?

The research team say their findings show that vagus nerve stimulation could be a cheap, safe and quick way to improve people’s heart health.

They add that this aligns with earlier research that found problems with the vagus nerve can increase the risk of exercise intolerance.

This includes a study published in 2017 in the journal Nature Communications of around 1300 people aged 63 years old on average, which looked at their heart rate during exercise and how quickly it returned to normal afterwards.

If it takes a longer time for heart rate to fall after exercise, this is a sign of lower vagus nerve activity.

The study measured how much people’s heart rates dropped in the minute after they stopped exercising. It found that a smaller fall in heart rate was linked to a lower VO2 max.

The researchers behind this new study suggest that stimulating the vagus nerve may help people with conditions that make it harder to exercise, like heart failure and coronary heart disease, improve their VO2 max.

This could help them stay active and look after their heart.

However, more research is needed to test the effects of vagus nerve stimulation in people with heart problems, they say.

How good was the research?

One of the study’s biggest limitations is that it included just 28 people aged 34 years old on average who had no health conditions that could lower their ability to exercise.

This means we cannot apply the study’s results to other groups of people, including those with heart problems.

However the study was strong in the way it was carried out, which meant the researchers had results from both the real and dummy electrical stimulation devices for the same person, which made the comparisons more robust.

The researchers did this by asking the participants to wear a device on both ears for 30 minutes at the same time every day for a week. Half of the participants wore a device that sent an unnoticeable electrical current to stimulate their vagus nerve, while the other half wore a dummy device.

Neither group knew which device they were wearing and their device did not change during the week they were wearing it.

They measured participants’ VO2 max, heart rate and breathing rate while they were using an exercise bike before and after they used each device for a week.

Then, after a 2-week break, they switched to the other device and repeated the process.

This meant the researchers did not have to compare results between different people with different levels of exercise tolerance.

How good was the media coverage?

The study was covered widely in the UK media, with reports in the Daily Mail, The Times and The Telegraph.

Most of the reporting was fairly accurate, but the Daily Mail’s headline – “Zapping the brain with a tiny device on the ear could boost fitness, study claims” – was misleading. The device stimulated the vagus nerve, not the brain.

And while The Times wrote that vagus nerve stimulation was linked to lower levels of inflammation in the blood, they did not include the fact that samples were only taken from 5 people, which is a tiny sample size.

The BHF verdict

Although the study is small, it suggests that stimulating the vagus nerve could help improve people’s ability to exercise.

In a BHF press release, Professor Bryan Williams, BHF’s Chief Scientific and Medical Officer, commented: “This early study suggests that a simple technology, which harnesses the connection between the heart and the brain, can lead to improvements in fitness and exercise tolerance.”

“While more research is needed involving people with cardiovascular disease, this could one day be used as a tool to improve wellbeing and quality of life for people with heart failure.”

What to read next...