This year the British Cardiovascular Society (BCS) conference went online for the first time, jam-packed with innovations in everything cardiovascular from imaging, to drug treatments and diagnostic tools.

The annual conference brings together members of the cardiovascular medical and research communities to interact and share best practice. Here are 9 things we learnt at this year’s conference.

1. A simple blood test could detect life-threatening aortic tears

Acute aortic syndrome (AAS) is a serious condition affecting 3000 people in the UK every year. It occurs when the wall of the aorta tears and blood begins to flow between the layers of the blood vessel wall. Patients with AAS need immediate treatment - in the most severe cases emergency surgery - to prevent the artery from rupturing and the patient potentially dying.

Diagnosis is a major challenge, but researchers we fund at the Universities of Dundee and Edinburgh have found that testing for a molecule called ‘desmosine’ may speed up diagnosis of this deadly disease. Researchers found that those suffering from AAS had almost double the concentration of desmosine in their blood.

“We urgently need a new, faster way to diagnose this catastrophic disease so that we can get patients the swift, life-saving treatment that they need. We need to confirm these results in bigger trials, but we hope that we have a potential biomarker that may help us detect a dangerous disease.” - Mr Maaz Syed, BHF Clinical Research Fellow

2. Injectable microspheres to repair failing hearts

Heart failure affects an estimated 920,000 people in the UK and can be debilitating.

For years scientists have been trying to find a way to use stem cells to repair damaged heart, and now research funded by us at University College London may provide the answer.

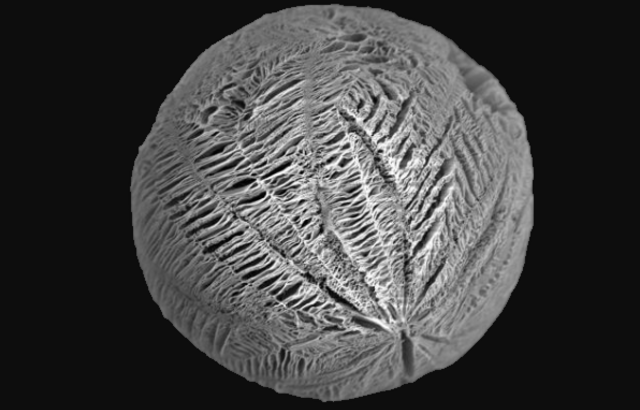

The team have grown human stem cell-derived heart cells on tiny microspheres, each only a quarter of a millimetre wide, engineered from biological material. Their tiny size means that they can be inject directly into the heart. A dye was also added so they can be visualised to check that they stay in place.

“Breakthroughs like this bring us closer to finding much-needed cures for heart failure and provide light at the end of the tunnel for the hundreds of thousands of people living with this debilitating condition.” – Professor Metin Avkiran, our Associate Medical Director

3. AI detects life-threatening blood vessel inflammation from Covid-19 variants

One of the finalists for the Young Investigator Award was for new artificial intelligence technology developed by our researchers at the University of Oxford that calculate a person’s risk of death from Covid-19 and its variants.

Over the past year we have supported our scientists to direct their expertise to help the global effort in understanding Covid-19. By using routine chest CT scans, the researchers have developed a Covid-19 ‘signature’ using machine learning. The ‘signature’ detects biological red flags in the fat surrounding the blood vessels in the chest to measure the level of vascular inflammation in people infected with the virus.

“By simply adding in one extra step to the routine care of people admitted to hospital with Covid-19 who already have a CT scan, we can now detect patients at high risk of life-threatening complications and could potentially tailor their treatment to aid long-term recovery.”- Professor Charalambos Antoniades, University of Oxford

4. Drug used to reduce blood sugar levels in diabetic patients could also benefit hearts

More than 3.7 million people in the UK have been diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes. The condition poses a significant risk factor for heart disease, as it can damage the walls of the arteries and lead to a heart attack or heart failure.

Researchers we fund at the University of Leeds have discovered that empagliflozin, which is typically prescribed to help reduce blood sugar levels, could enhance the energetics and function of these patients’ hearts.

The drug was given to 18 people living with Type 2 diabetes, and they were monitored over three months. Before treatment the patients had lower energy levels in their heart than those living without the condition and had a lower percentage of blood being pumped from their heart each time it contracts. Twelve weeks later, most patients had significant improvements in the heart’s energy levels, and the heart was able to pump blood more efficiently.

“This study builds on emerging evidence about the benefits empagliflozin can have on the heart. Further research will be needed on a larger cohort of patients to identify who may benefit the most from taking this medication, but this is a promising step.” - Professor Jeremy Pearson, our Associate Medical Director

5. Drugs to stabilise plaques could prevent stroke

Each year in the UK more than 100,000 people have a stroke, and it’s estimated that a quarter of these are caused by a build-up of atherosclerotic plaques in the carotid arteries – the main blood vessels in the neck. Right now, the only way to prevent unstable plaques from disintegrating and causing a stroke is to remove them in surgery.

However, researchers at the University of Sheffield found that by ‘re-programming’ white blood cells, they were able to switch them from a pro-inflammatory to an anti-inflammatory state. This made them less likely to rupture and block blood-flow to the brain.

The researchers hope that in the future anti-inflammatory drugs could be used to stabilise plaques and reduce the risk of a stroke occurring without the need for risky surgery.

“This research is at an early stage now but if these findings can be replicated and extended in people we may finally have found a way to reduce risk of the risk of stroke for many thousands of people each year.” - Professor James Leiper, our Associate Medical Director

6. Your smart watch could alert you to risk of sudden death

Every year in the UK thousands of people die of sudden cardiac death, where the heart develops a chaotic rhythm that impairs it ability to pump blood. Usually, identifying people at risk of sudden cardiac death requires a visit to hospital for tests.

Researchers from Queen Mary University of London and University College London have developed an algorithm that could, in future, enable smart watches to detect potentially deadly changes in the wearer’s heart rhythm, and identify people at risk of sudden death. It works by identifying changes in electrocardiograms (ECGs, which measure electrical activity in the heart) that were associated with an increased risk of being hospitalised or dying due to an abnormal heart rhythm.

The team used data from nearly 24,000 participants from the UK Biobank Imaging study, which was part-funded by us, to get a reference for normal ECG waves. By applying the algorithm to ECG data from over 50,000 other people in the UK Biobank study they found that people with the biggest changes in ECG waves over time were significantly more likely to be hospitalised or die due to ventricular arrhythmias. The work was also selected as one of the finalists for the Young Investigator Award.

7. Heart cell changes identified in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a condition in which the heart muscle becomes thinned and weakened so the heart becomes ‘baggy’ and is unable to pump blood around the body efficiently. An estimated 270,000 people have DCM in the UK and is a common cause of heart transplantation.

Inherited DCM can be caused by a change or mutation in one or more genes. More commonly, DCM is caused by other conditions, such as heart attacks, diabetes or viral infections. However, as DCM develops, what happens at the cell and molecular level in the heart is poorly understood.

Scientists funded by us at Queen’s University Belfast have been studying data from thousands of individual heart cells from people with DCM and have shown changes in gene expression, the way in which information stored in DNA is converted into instructions for making proteins, in people with DCM.

8. Invisible insulin resistance linked to increased risk of sudden death

Years before developing diabetes, people with insulin resistance could be more likely to develop abnormal heart rhythms, which may put them at greater risk of sudden death.

Now, using blood samples and ECGs, our researchers in London have found that low levels of the hormones leptin and insulin-like growth factor 1, which are signs of insulin resistance, were strongly associated with an abnormal ECG– an indicator that in individual is at risk of developing arrhythmia and sudden death.

This is the largest study to date to show that people with insulin resistance, who are otherwise apparently healthy, may be at higher risk of developing dangerous arrhythmias, and therefore sudden death.

“Many people don’t know that they have insulin resistance until it has developed into diabetes. We need to make it easier for people to maintain a healthy diet, weight and to get more exercise to reduce their risk of developing it.” - Dr Sonya Babu-Narayan, our Associate Medical Director and Cardiologist

9. Prof Marianna Fontana awarded the Michael Davies Early Career Award

On day three of the conference, Professor Marianna Fontana, BHF Intermediate Clinical Research Fellow was awarded the prestigious Michael Davies Early Career Award in recognition of her outstanding contribution to cardiovascular science.

Her work focusses on amyloidosis, a rare condition caused by deposits of amyloid protein that stiffens the heart muscle. Amyloid mainly collects in the heart and nervous system and leads to a range of symptoms including chest pain, abnormal heart rhythm and heart failure.

Prof Fontana has developed a new cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging technique that is able to measure amyloidosis in the heart muscle. It has shown that the condition varies a lot from person to person, and that many different mechanisms combine to cause heart failure.

If you liked this blog post, you can find out more about the research we fund here.