“I’m so stressed” is a phrase we hear all the time. We say it almost without thinking, perhaps while making that fourth emergency coffee. But what does it mean to be stressed? And what does it mean for our health?

In part one of our series on stress and the heart, we look at psychological stress: the ancient defence still trying to protect us to this day.

Part 1: Psychological stress

We know that being under stress, whether work-related, financial, or emotional can lead to ill health. When faced with something threatening, the body responds with what you may know as the ‘fight or flight’ response: a rapid change in heart rate caused by adrenaline coursing through our bodies and preparing us to fight, or run, for our lives.

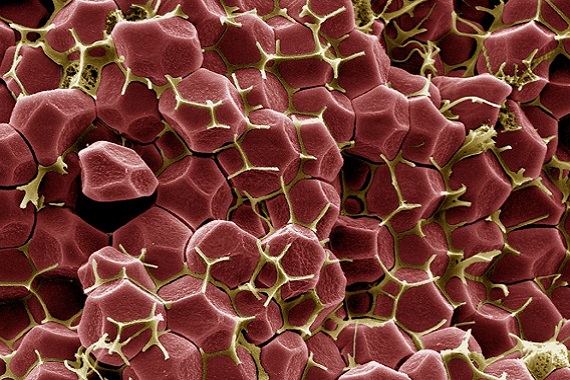

Stress is recognised by our brains, and this triggers a signal in our nervous system to encourage our body to make more white blood cells. Historically. this ancient response prepared us to fight off infections in wounds from dangerous animals, but when it is caused by modern day stress, in the absence of that lion or bear, we simply increase the number of cells that make our body inflamed. The white blood cells born of stress may also be more inflammatory than usual, and bad at receiving anti-inflammatory signals that naturally hold our white blood cells in check.

Unfortunately, our modern, busy, lives can keep this fight or flight response going on at a low level that we barely notice, all the time.

Blood vessel health

Why does this matter for heart and circulatory health? Because those angry white blood cells circulate in your blood vessels, and can contribute to vessel diseases. We funded PhD student Amy Ronaldson to examine the link between stress and risk of cardiovascular disease.

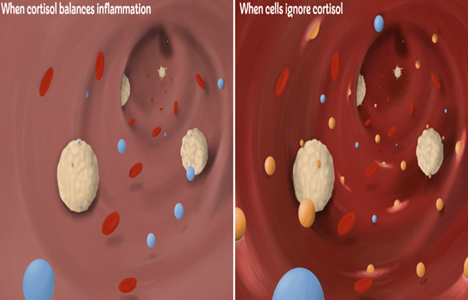

When immune cells (white) ignore the calming effect of cortisol (in blue), they release inflammatory molecules like cytokines (in orange) and contribute to blood vessel inflammation.

BHF Professor Gianni Angelini has also studied inflammation. He has seen that heart surgery can lead to body-wide inflammation and longer hospital stays. We funded Professor Angelini to examine the levels of cortisol in someone’s body throughout the day, and to test whether the levels being released were too low in very ill patients post-heart surgery. His research found that the natural waves of cortisol release became disorganised in people who were critically ill following surgery, compared to those who recovered well. This research could help doctors provide patients with more appropriate treatments, which could help get them out of hospital quicker.

The stress cycle

Whilst cortisol is the calming hormone that restricts our stress response, adrenaline and noradrenaline have the opposite effect. These stress hormones increase heart rate and blood pressure. But this forms a cycle as high blood pressure also causes the release of noradrenaline. When someone with high blood pressure undergoes stress, the two conditions aggravate each other, causing damage to blood vessels.

This cycle may be due to problems in how the hormones are controlled. We funded Professor David Paterson to look into a fault in the pathway that removes noradrenaline from the blood. He believes that this insight could help us identify targets for new drugs and treatments for those with high blood pressure.

Stress comes in different shapes and sizes

The role of stress hormones in blood vessel damage is clearly important, but this isn’t the only stress that burdens our bodies. In part two we will look at a type of stress that can adversely affect the heart and circulatory systems of even the fittest and calmest of us.

More BHF Research

Ever wondered which animal has the most complex heart? Or how what you drink can affect your health? How about if you can die from a broken heart?

Our brightest and best life saving research is brought to you each week.