What’s most exciting in

angina research right now?

Angina is a symptom experienced

when the blood vessels that supply the heart, the coronary arteries, narrow

and not enough blood gets to the

heart muscle. Most people have a type

called stable angina where

the narrowing of arteries happens

slowly over time.

Doctors previously focused on

opening the arteries of people with

stable angina in order to prevent heart

attacks from happening.

Now we are placing more emphasis

on people’s symptoms.

As a doctor and researcher, it’s rewarding to help people get back to what they enjoy.

When you speak

to people with angina, over a third will

tell you it seriously affects their quality

of life.

Because of the chest pain and

breathlessness they experience with

angina, they are no longer able to pick

up their grandchildren, or run for the

bus, for example.

Giving people with angina the right

medication or procedure lets them get

back to what they enjoy.

I’ve had patients tell me they’ve been

able to get back to playing in a band

because they can now lift their double

bass, or even that they completed

the National Three Peaks Climbing

Challenge after having the right

treatment. As a doctor and researcher,

that’s very rewarding.

How will research change the

way angina is treated?

I think the biggest difference is that

in 20- or 30-years’ time treatment will

be more personalised.

At the moment,

treatment for stable angina tends to be

one-size-fits-all, with most people put

on the same pathway.

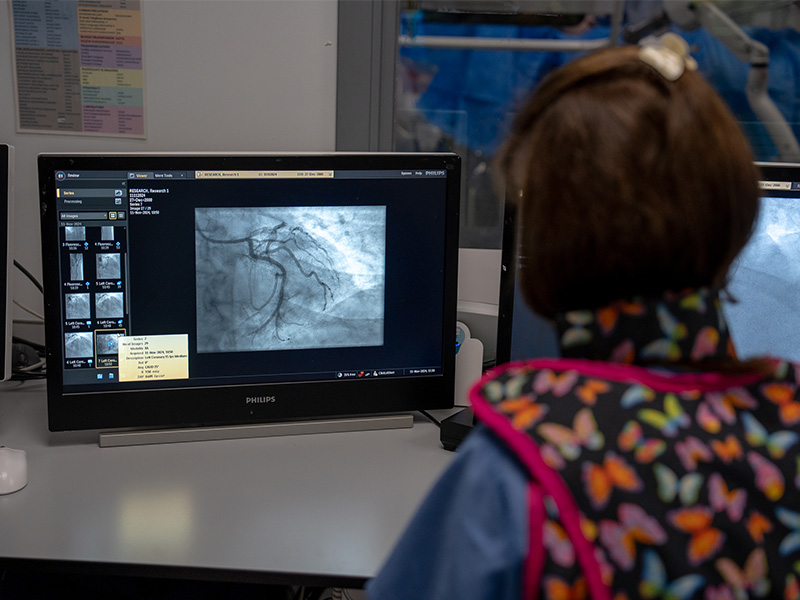

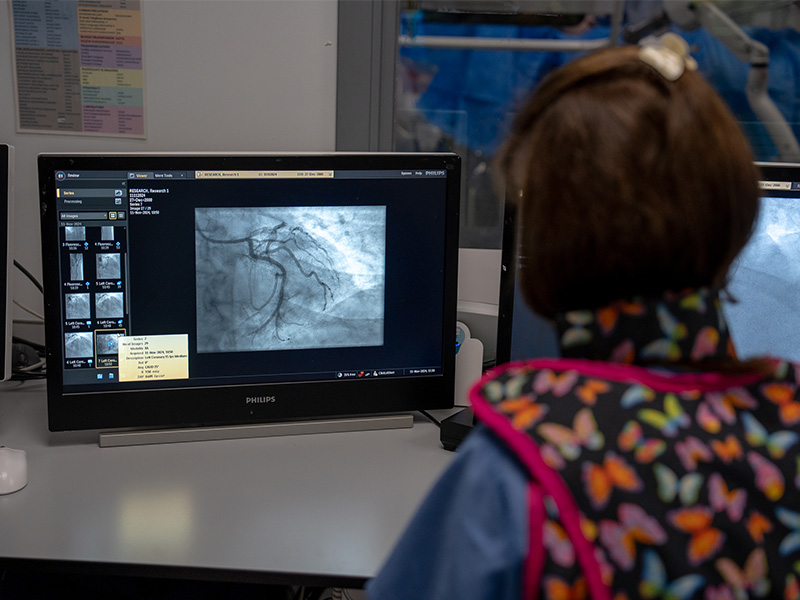

Clinical guidance tells us to try

medicines first. Then, if that does not

work, they are offered a procedure

called angioplasty and stenting, where

a small tube called a stent is used to

reopen the arteries.

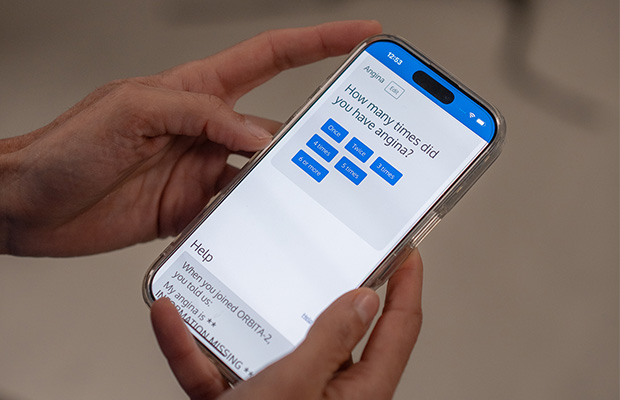

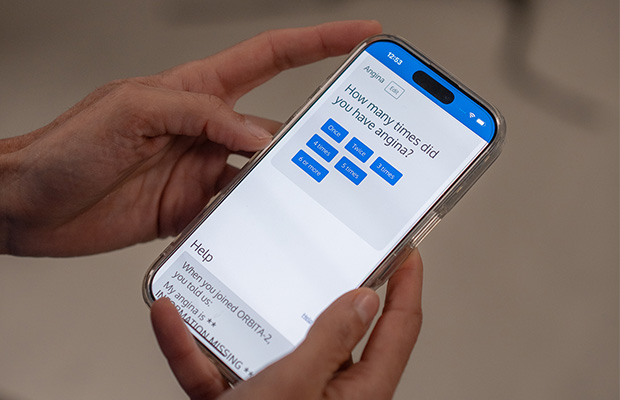

But through trials

I’ve conducted, called ORBITA and

ORBITA-2, it seems some people would

benefit from being offered a stent first.

This is particularly true of those

who experience pain in the middle of

the chest when they exert themselves,

which goes away when they rest.

I’d like to get to the point where the number of people still living with angina symptoms disappears.

We’ve also learned that not

everyone feels better with stenting.

Somewhere between 30 to 60 per

cent of people still feel symptoms after having a successful procedure.

So BHF

is now funding my work to find out how

we can target stenting to the people

who will experience the most benefit.

I am looking at the symptoms people

experience, what imaging technology

tells us about the narrowing of their

arteries, how these and other factors

are connected, and how they could be

used to predict who stenting will help.

I’d like to get to the point where the

number of people who are still living

with angina symptoms, despite having

multiple different treatments, is far

smaller, and maybe even disappears.

Why is it important for BHF to

fund research like this?

This is not the kind of research that

the medical industry would fund.

This is because my research has found

that expensive treatments are not

always as useful as we might think.

Also, it might not happen in other

countries, where clinical research is

not so closely linked to the healthcare

system, as it is in the UK.

Independent charities like BHF

recognise the importance of research

that investigates questions that matter

to patients.

Thanks to BHF funding, science like this has the potential to shape best practice across the world.

What happens if anti-anginal

medicines and stenting fail?

Some people with coronary heart

disease have treatment, including

medicines, stenting or a coronary artery

bypass, to open their arteries but they

still experience chest pain.

We call this refractory angina. It can

really affect people’s lives as they have

no other options for treatment.

In one of our trials, ORBITA COSMIC,

we tested the use of a new device

called a coronary sinus reducer.

In

regular stenting a stent is used to

widen the narrowed artery supplying

the heart. By contrast, the hourglass-shaped coronary sinus reducer is used

to narrow the heart muscle’s main vein.

This helps blood flow to areas of the

heart muscle not getting enough blood. Research may help this to become a

regular treatment option in the future.

Want to get fit and healthy?

Sign up to our fortnightly Heart Matters newsletter to receive healthy recipes, new activity ideas, and expert tips for managing your health. Joining is free and takes 2 minutes.

I’d like to sign-up

Microvascular angina is

another growing area for research.

Most medicines have been

developed to treat narrowing in the

main arteries that supply the heart.

They do not target the problems in the

very smallest of arteries which happen

with microvascular angina.

Now there are trials taking place,

including one funded by BHF, to test

out the coronary sinus reducer in

people with microvascular angina.

Other researchers are using new

imaging technologies to better

understand what is happening in these

micro vessels. Others are looking at the

biological processes happening in the

body in microvascular disease. With

better understanding, we’ll be able to

develop new treatments.

How do we prevent angina from developing?

I'm working with the medical journal The Lancet on a commission on exactly this issue: How do we get to the point where coronary heart disease stops being a very common disease and it becomes very rare or even disappears?

A big part of the answer is to help people reduce high blood pressure and cholesterol levels and control diabetes, to prevent these risk factors leading to the coronary heart disease, which is one of the main causes of angina.

In recent years we’ve seen the development of exciting new cholesterol-lowering drugs and ones that target diabetes. Also, guidelines are changing so that we’ll be targeting patients to lower their blood pressure and cholesterol levels at an earlier stage.

What made you interested in researching angina?

I've always been interested in clinical trials and how the results can affect how we actually treat people. I wanted to study a disease that was common and to design clinical trials that would have an impact on the greatest number of people.

Over a million people in the UK live with angina and it can create a significant burden on their ability to live their lives.

Also, across the world, over 500,000 stenting procedures are done every year to treat angina. This has a big economic burden but importantly it carries some short and long term risks for patients, so we want to make sure we are only performing this procedure for the people who actually stand to benefit from it.

Meet the expert

Dr Rasha Al-Lamee is an interventional cardiology consultant at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust in London. Alongside seeing patients, she is funded by British Heart Foundation (BHF) as a research fellow at Imperial College London.

What to read next...