Protecting our health from air pollution

We’ve been funding research to show how air pollution can damage your heart and blood vessels, as well as campaigning to influence Government policy.

Studying health information from large numbers of people is a valuable tool to find new insights about health and disease. This can lead to improvements in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment for patients. The potential benefits are huge, but we are still learning how best to make use of the vast amount of health and research data now available.

This can include data about the genetics, health and lifestyle of large numbers of people in the UK, either from people who have volunteered to share their biomedical data (such as those in UK Biobank) or taken part in clinical trials, as well as data from healthcare records. The data is held securely and anonymised before making it available to researchers.

New technologies including artificial intelligence and machine learning are helping researchers identify patterns hidden in the data.

BHF Professor John Danesh, at the University of Cambridge, leads a study of risk factors for heart and circulatory diseases in more than half a million people from 10 European countries, supported by the BHF and other funders. The aim of this study, called EPIC-CVD, is to advance our knowledge of how genes and lifestyle factors work together to cause heart and circulatory diseases. Professor Danesh and his team showed in 2018 that UK guidelines for alcohol consumption limits may be too high and that drinking within the guidelines could still increase the risk of some heart and circulatory conditions.

Since 2003, the BHF has part-funded another big data initiative - the Emerging Risk Factors Consortium, also led by Professor Danesh. Scientists from 25 countries have pooled information on risk factors from 2.5 million individuals. This project has generated new insights into the risk of heart and circulatory conditions. In 2020, the team showed that people with depressive symptoms have a small increased risk of developing heart and circulatory diseases in the future. However, these results are just one piece of the puzzle and more research will be needed to understand whether or not depression itself raises your risk of heart and circulatory diseases, and if so, what the biological reasons behind it are.

We are one of a group of funders who support UK Biobank, a huge study that has collected anonymised health and lifestyle data and biological samples from 500,000 volunteers. In 2016, the BHF funded a heart imaging study in 100,000 of the Biobank participants. These volunteers had magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans to look at their heart size, heart function, heart weight and stiffness of their blood vessels.

In 2018, a team of scientists, led by Professor Steffen Petersen at Queen Mary University, London, studied cardiac MRI data from around 4,000 participants in the UK Biobank study.

The study showed that air pollution was linked to changes in the structure of the heart, similar to those seen in the early stages of heart failure. And these changes were seen even in people who lived outside of major UK cities and where air pollution levels were within UK guidelines.

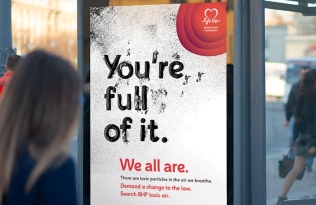

Higher exposures to the pollutants were linked to more significant changes in the structure of the heart, and those living close to a busy road were more likely to have changes to their hearts. These findings were highlighted to Government in our 2020 campaign called ‘We’re full of it’ where we called for the World Health Organization’s guideline limits for fine particulate matter (one of the damaging ingredients of air pollution) to be adopted into UK law and reached by 2030.

UK Biobank is a valuable resource that is available to researchers from all over the world, who can return time after time to ask different questions. We will all continue to benefit from this data as new areas of research are identified.

For example, the team behind UK Biobank plans to carry out MRI imaging of at least 3,000 of its volunteers, who were also scanned before the Covid-19 pandemic. Their scans before and after the pandemic will be compared with each other, and matched against whether or not they suffered Covid-19, to look for changes in the heart post-infection. This will add to our understanding of the medium and long-term effects of Covid-19.

First published 1st June 2021