Worldwide, high blood pressure is responsible for around 7.6 million premature deaths every year. It’s a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, which is why it’s important to know your blood pressure and try to keep it down. But is there a risk in going too low?

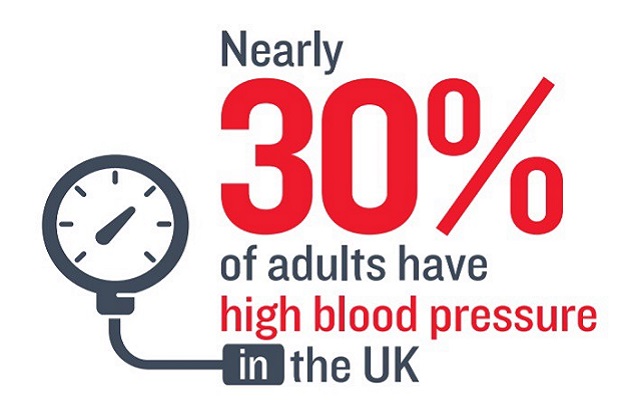

High blood pressure — or hypertension — means that your blood pressure is consistently higher than the recommended level. In the UK, that means having a blood pressure that is regularly above 140/90mmHg.

High blood pressure isn’t normally something you can feel or notice but, if left untreated, it can lead to an enlarged heart and even heart failure. The good news is that most of the causes of hypertension are related to our lifestyle, which means we can do something about them. Regular exercise, maintaining a healthy weight, cutting down on salt and drinking less alcohol can all help to lower blood pressure. There are also treatments available to help you get below the target of 140/90mmHg.

But why stop there?

Researchers at the ESC Congress in Barcelona have now argued that blood pressure guidelines for patients in Europe and North America are still too high, leaving large numbers of people at risk of CVD. Some have suggested that we should follow the lead of countries like Australia and Canada, where the guidelines recommend a blood pressure of below 120/80mmHg. But the evidence is by no means clear cut.

How low can you go?

Low blood pressure is normally nothing to worry about, and is often thought of as a sign of good health. But lowering your blood pressure intensively leads to hypotension — the opposite of hypertension — and this can cause dizziness, fainting, problems with the uptake of electrolytes and, in some cases, may require you to go to hospital. There is also research that suggests that diabetics with low blood pressure can actually see their risk of CVD increase slightly.

As with so many things in life, there is a balance to be struck. Doctors have to weigh up the potential benefits of lowering blood pressure with the health risks, as well as the cost of treatment.

When your blood pressure is consistently down to between 130/85–139/90mmHg, you are at significantly lower risk of cardiovascular disease. If you then drop down to 120/80mmHg, the evidence suggests your CVD risk doesn’t reduce much further. So there doesn’t seem to be a major health benefit in going this low, while the cost of treating someone to reach this target can be significantly higher.

Relieving the pressure

It may not come as a surprise but when and where you measure someone’s blood pressure is very important. Our blood pressure varies widely at different times of day and in different settings, such as at work or in a GP waiting room.

Some people have a condition known as ‘white coat hypertension’, which causes your blood pressure to rise when a doctor or nurse is measuring it and not because you have an underlying medical problem. For people employed in high-pressure jobs, a low reading during a consultation with their doctor may underestimate their average blood pressure across a normal working day.

Getting an accurate reading can be very difficult for some people so you may need to have your blood pressure rechecked several times, or you have to wear a 24-hour blood pressure monitor.

Setting targets

There’s no question that lower is better. But when it comes to setting the guidelines for just how low we should go, we need to at least know that we can measure blood pressure accurately, otherwise the number is in many ways irrelevant.

Everyone is different and doctors don’t blindly follow guidelines when treating patients. They will look at your overall health and other risk factors for heart disease before deciding on a course of treatment that makes the most sense for each individual.

The guidelines do, however, provide the benchmark from which to work and that’s why this debate is so important.

Read more about high blood pressure

More BHF Research

Ever wondered which animal has the most complex heart? Or how what you drink can affect your health? How about if you can die from a broken heart?

Our brightest and best life saving research is brought to you each week.