How to lower your cholesterol - food, exercise and common questions

Our cardiac nurses answer your questions about how to lower your cholesterol, including simple food and exercise tips.

Understanding more about what causes heart and circulatory diseases is vital to helping us prevent and treat them.

Thanks to research by the BHF and others, we now know much more about treating some of the important factors that can lead to heart attacks and strokes - such as high cholesterol.

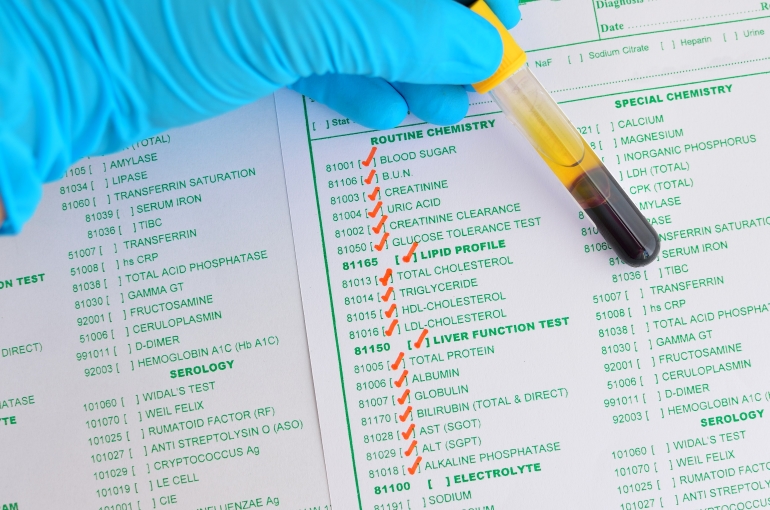

Your blood contains thousands of different molecules (sometimes called biomarkers) and these can be measured. Cholesterol is an example of a biomarker that directly causes heart and circulatory disease. We know that lowering cholesterol, for example with statins, reduces the risk of heart attacks and strokes.

But there are other biomarkers which we know are raised in people with heart and circulatory disease, but it isn’t always clear whether this is because they cause the disease, or are a sign of disease. We are funding research to find new biomarkers and to discover whether they increase the risk of disease, in which case they could be targeted in future by new medicines.

One way to do this is to use genomics – the study of the over 3 billion ‘letters’ that form our DNA and genes. Variations in single letters in our genes can lead to a difference in the level of a biomarker. If the risk of disease, for example a heart attack, is higher in people with a particular gene variant, it is very likely that the gene is directly involved in causing disease. That means that the biomarker the gene is linked to is also likely to be a cause of disease, rather than an effect of disease.

BHF Professor Hugh Watkins and colleagues at the University of Oxford used the gene sequencing in 2009 to show that gene variants that lead to increased levels of a biomarker called lipoprotein (a) or LP(a), are strongly linked with coronary heart disease. This suggested that lowering levels of LP(a) could be useful in reducing risk of heart disease. This led directly to drug companies around the world designing drugs to lower LP (a). The first of these are now being tested in clinical trials to see whether lowering LP(a) can reduce the risk of coronary heart disease.

We are also funding Professor Aroon Hingorani’s team at University College London, to use new mathematical methods to improve the accuracy of genomic studies to find new avenues for treatment, and to understand whether drugs already in use for other diseases could have new uses.

C-Reactive Protein (CRP) is a biomarker that has been known for years to be raised in people at high risk of heart disease, but scientists were unsure whether it was a cause or effect of heart disease. In 2011, BHF Professor John Danesh at the University of Cambridge, in collaboration with an international consortium, was able to sequence the CRP gene in almost 200,000 people to answer this question. They showed that gene variants that caused naturally high levels of CRP in the blood were not associated with an increased risk of heart disease, proving that high CRP levels do not cause coronary heart disease. This has meant that scientists don’t need to look for CRP treatments as a way of preventing heart disease, and can focus their efforts on finding other new treatments instead.

Our research is using the enormous power of genomics to help doctors to identify which of us are at most risk of heart and circulatory diseases, and is helping scientists find the way towards potential new treatments.

First published 1st June 2021