Heart valve disease - BHF-PROTECT-TAVI

Can a device help make transcatheter aortic valve implantation safer?

The clinical question

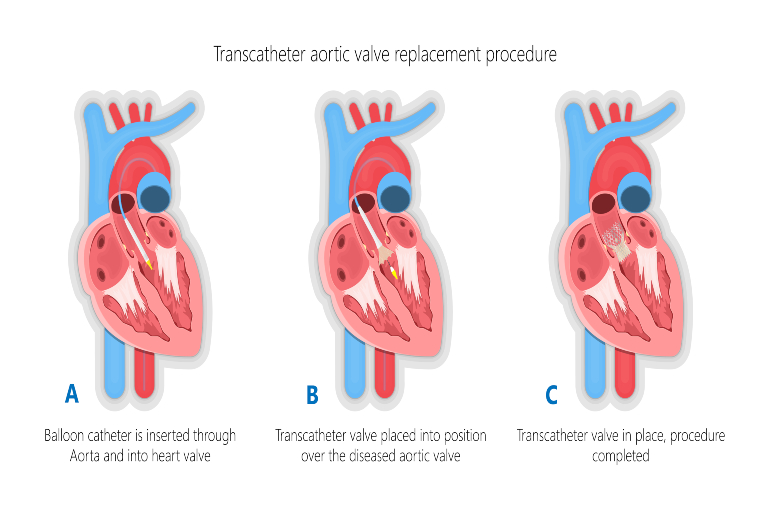

Your heart has four valves which help blood move in the right direction through your heart. The aortic valve controls the flow of oxygen rich blood out of the heart. Aortic stenosis (AS) is a condition where the aortic valve becomes narrowed, restricting blood flow out of the heart. AS can be treated by replacing the damaged valve. This is done either by performing open heart surgery, or by a less invasive procedure called transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI).

During TAVI, a narrow flexible tube (called a catheter) is put into a blood vessel in the upper leg or chest and is passed towards the heart. The tube is used to fix a replacement valve over the top of the old narrowed aortic valve. TAVI has a quicker recovery time than open heart surgery, but it has some risks. This includes a small risk of experiencing a stroke, which happens to around 2 to 3 in every 100 people having a TAVI.

A BHF-funded team of researchers, led by Professor Rajesh Kharbanda from the University of Oxford, wanted to test whether a device called a cerebral embolic protection (CEP) device could reduce the risk of stroke related to TAVI. This device consists of filters, which are inserted into arteries supplying the brain during TAVI. It is designed to help prevent any debris released into the bloodstream during the TAVI procedure from reaching the brain – in theory, helping to prevent this debris blocking the brain’s blood supply and causing a stroke. But it wasn’t known whether routinely using this device during TAVI actually helps to prevent strokes related to the TAVI procedure. The BHF-PROTECT-TAVI trial was designed to provide a definitive answer to this question so that it would be possible to decide if this treatment would be used in the UK.

Watch a video explaining the trial

What did the study involve?

Between October 2020 and October 2024, 7635 people were enrolled across 33 UK hospitals (32 NHS and 1 private). Over the time the trial was running, around 30% of all TAVI procedures happening at the NHS hospitals involved were part of the trial.

Participants were randomly assigned to two groups:

- Half were assigned to have TAVI, with no CEP device

- Half were assigned to have a Sentinel CEP device during their TAVI. This device is inserted through a blood vessel in the arm at the beginning of the TAVI procedure. The device is removed, along with any debris it catches, at the end of the procedure.

After their TAVI:

- Participants were followed up in hospital for up to 72 hours (or up to when they were discharged, if sooner) to assess whether they had a stroke.

- At 6-8 weeks and a year after their TAVI, participants were contacted by phone to complete questionnaires about their quality of life and thinking ability. This could also be done in person if participants already had a hospital visit arranged.Participants also gave their consent for the research team to access information about their health from their NHS records.

What did the study show?

- Receiving a CEP device during TAVI did not seem to have an impact on participants’ likelihood of having a stroke associated with the procedure. 81 of 3795 participants (2.1 per cent) who received a CEP had a stroke, compared to 82 of 3799 participants (2.2 per cent) who did not receive a CEP.

- The number of participants who died or had a stroke leading to disability up to 8 weeks after the TAVI procedure was similar between groups.

- The number of participants who experienced complications, such as bleeding or pain where the catheter for the TAVI or CEP device was inserted was also similar between groups.

- The researchers are continuing to follow up participants in the trial up to a year after their TAVI, to see if there are any differences in outcomes in the longer term.

Why is the study important?

This trial answered an important clinical question and showed how clinical trials delivered in the NHS can deliver world-class findings, that directly lead to changes in treatment for people affected by cardiovascular disease both in the UK and beyond. Prior to BHF-PROTECT-TAVI, CEP devices were not being routinely used in the NHS but have been more widely used in North America and Europe. These devices are relatively expensive and require additional training for doctors performing TAVI to use them. So there was a real need for good evidence whether they are beneficial at preventing stroke or not, to decide whether they should be used more widely.

Professor Kharbanda presented the results of BHF-PROTECT-TAVI at the American College of Cardiology Scientific Sessions in Chicago in March 2025. He said: “This large, well-conducted clinical trial has addressed the question of whether routinely using this CEP device in all patients having a TAVI is effective at reducing the risk of stroke.”

“Our study provides convincing evidence that there is no value in the routine use of current CEP devices during TAVI.”Professor Rajesh Kharbanda, Chief Investigator, BHF-PROTECT-TAVI

In May 2025, Professor Kharbanda also presented findings from combining the results of BHF-PROTECT-TAVI with another clinical trial called PROTECTED TAVR, which involved 3000 people undergoing TAVI with and without a CEP device across North American, Europe and Australia between 2020 and 2022. ‘Pooling’ data from multiple independent studies in this way is known as meta-analysis and can allow broader conclusions to be drawn about a research question than a single study. This analysis involved 10,000 people across the two trials, and confirmed that overall, there was no difference in the risk of stroke between those having TAVI with and without a CEP device.

These results probably also reflect that the risk of stroke following TAVI is reducing over time, due to improvements in TAVI valves and how these procedures are carried out. The trial was funded by BHF in 2020, and at that time the researchers estimated that about 3% of people having TAVI would experience a stroke. As the number of people who had a stroke was lower during the trial (about 2%), this means it would be harder to see any benefit of using CEP in everyone having a TAVI.

Professor Kharbanda added: "It is possible that next-generation CEP devices could potentially reduce stroke risk for certain groups at higher risk of stroke following TAVI. But we need to better understand which people are at higher risk, and further trials to test whether more targeted use of delivering CEP to those people is beneficial. This will be the basis of our ongoing research.”

This excellent trial demonstrates the importance of BHF research funding to answer internationally relevant clinical questions.Professor Bryan Williams, Chief Scientific and Medical Officer, British Heart Foundation

Study details

"British Heart Foundation Randomised Clinical Trial of Cerebral Embolic Protection in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (BHF PROTECT-TAVI)”

Award reference: CS/20/1/34732

Principal Investigator: Professor Rajesh Kharbanda, University of Oxford

Trial registration number: ISRCTN16665769

Publication details

Kharbanda RK et al. Routine Cerebral Embolic Protection during Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Implantation. N Engl J Med. March 2025.